Living in Kuwait has made it so much easier for me to pursue my passion for motorcycle travel. I bought my first big bike in Kuwait back in 1998, and began my slow but beautiful journey of riding around the world. From my early trips of putting the bike on a ferry to tour Iran, to my drives across the Middle Eastern region, to flying my bike out to Europe and the rest of the world. Throughout all of these trips, the support I receive from my friends at Tri Star Motorcycles is phenomenal. After celebrating my 50th birthday, I decided to take my travels further—I wanted to share my experiences with a broader audience through social and print media.

Last September, I was on the verge of signing with a major Satellite TV station in the hopes of creating a travel documentary series based on my travels, and after taking two months leave from work they abruptly cancelled. Disappointed at first, I soon realized that it was a blessing in disguise. I took matters into my own hands and produced it myself. 48 hours later, I arranged an epic journey across the Indian Himalayas in Ladakh, Jamu and Kashmir to ride the world’s highest highway to create a film documentary. Moreover I garnered the support of an award-winning director and with his expertise, a documentary was under process. I gathered all of the equipment I could source, from my personal camera, my son’s Go Pro to a collection of iPhones. We decided to sponsor my friend Ebrahim Al Kandari’s initiative iDream Kuwait, where he is training Kuwaitis with disabilities to work in the private sector. After arranging a meeting with our CEO and securing support on a corporate level, I am personally dedicating this film to support and raise awareness for his cause.

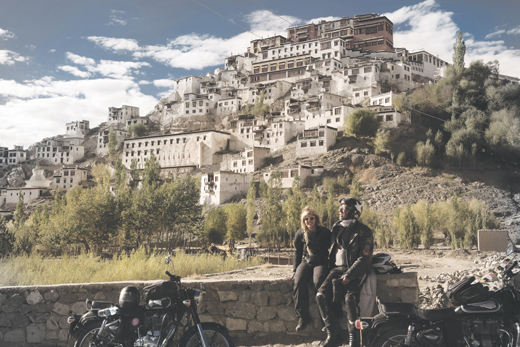

The Motorcycle is the perfect solution for my desire to fly while avoiding my fear of heights, I chose India and specifically Ladakh, which means the land of high passes, so that I could ride the world’s highest road and soar like an eagle without having to fly. We had to deal with the reality of altitude sickness and take it very seriously, as the sudden ascent from living at sea level in Kuwait to starting our journey over 3,500 meters required gradual acclimatization and precautions. In our situation, time was off the essence. I prepared a full support vehicle with spare parts, oxygen tanks, and a mechanic, with the support of an incredibly helpful multicultural crew to reduce the risk especially for my wife who had decided to join me on this journey. We were very fortunate to arrive at Leh during their annual festival (20th-26th of September). Throughout most of the year, this region is usually closed off by snow. September in Ladakh represents a time when the locals go out and celebrate, from traditional sports like archery and polo to music, food, and famous monastic dances in the monasteries using ritual instruments—it was truly a rare and beautiful sight to experience.

A STURDY MULE

The Royal Enfield, my main source of transport for this trip, worked like a sturdy mule—it never gave up. Built originally for World War II, the company decided to open in India and was later bought by the locals. I was astonished to learn that they still build the bike the same way they did during the war era, no additional innovations or technology, no thrills or fancy bells and whistles. The 1 cylinder 500 cc impressed me so much as we drove it across every possible terrain one could imagine. The bike endured a harrowing cocktail of black ice, fresh snow, mud, sleet, rock, gravel, and sand.

ACCLIMATIZING IN LADAKH

Our first bike run totaled 150 km around Leh and allowed us to explore the esoteric palatial Hemis monastery, a Tibetan Buddhist monastery founded in 1672. The monastery represents traditional Tibetan architecture; the building is load bearing structurally and crafted from local stones. The walls are extremely thick to provide insulation from the cold winters, and what is most remarkable is the fact that this monastery is known for a festival that takes place every twelve years. I imagined the huge courtyard enveloping the monastery alive with music and local monastic dances, and hoped to witness it one day. The structure also brought to my mind a striking similarity between old Kuwaiti architecture and the palace grounds, as they both shared common elements such as the courtyard, the wooden columns, roof structures, and particularly the articulation of columns. While the columns at Hemis were more colorful, the strong correlation denotes the historic relationship between Kuwait and India. The materials and methodology were transient, just like the Silk Road and trade routes of days past.

AN EVENING AT PANGONG TSO LAKE WITH THE CHUNGPA NOMADS

We were surprised to learn that our issued visas would expire sooner than we had anticipated, so we set out on our journey to Ladakh’s third highest pass, also known as Spagmik, to get used to riding the rough and battered roads of the mighty Himalayas. Before we could attempt the world’s highest road, we started with the third highest road in an effort to build our tolerance toward the impending altitude sickness, get used to the roads, and immerse ourselves with the local culture in preparation for our final journey. It is truly a land where nature dominates man and must be treated with the utmost respect and admiration. We ran the risk of altitude sickness faster than we should, so we employed the use of oxygen tanks. On our way to Pangong Tso Lake, we ended up spending the night with the local Chungpa nomads.

Located close to Chinese border, the area has restricted access and proved challenging. The altitude alone was more than 4,500 meters. As soon as we arrived to the lake, it was sunset. A local legend traces the history of the lake to millennia ago. It is said that the huge saltwater lake that stretches over 100 KM in length with only a quarter of its size in India formed as a result of the collision of two continental plates. As the local families regaled us with their stories, I admired the traditional house that followed Buddhist tradition. The kitchen and bathroom are both located in separate buildings, and there also were the nomads’ source of livelihood that is their livestock of yak and sheep, and only a few cows.

Hospitality is a deeply rooted part of the Chungpa tradition. They do not dine with their guests, and the food is cooked fresh by the wife in the traditional kitchen that is laden with antique pieces of china and other fine kitchenwares that are inherited through generations. Extreme temperatures are combatted with a portable heater that utilizes yak waste to keep the space warm, and it is moved from one structure to the other. I enjoyed our stay there, and especially connected with their young son, who was completely fascinated with our fancy iPhones. We enjoyed our little sips of local Ladakhi Chai that is sweetened with butter for added insulation and warmth, as opposed to the traditionally Indian Masala Chai, and we called it a night.

The nomadic tribe has a close symbiotic relationship with nature. It is their way of life. The goats and Yaks that are herded are provided with shelter and protection from snow leopards and wolves. In exchange they use their milk, their excrements for fertilization and even heating, their wool is slowly gathered over time to weave the intricately built shelter and blankets, and a goat is slaughtered every sixth months while others are preserved for religious reasons. Blessing rituals are observed every morning. The father read his prayers, navigating the premise in a clockwise manner. The mother milked the goats. It is a simple society, and matriarchal in nature as well, as some tribes allow the woman to take two husbands, while some men take up their roles at the monastery.

SUMOOR VIA SHYOK

An area that was previously hit by a storm in 2010, severe flashfloods and landslides were common, but we didn’t expect to encounter a landslide in the making. As I road ahead, I noticed the ragged and breathtaking scenery, but as I was ascending a gravelly hill, I dropped the bike and triggered a stone landslide. As the stones fell, I picked up the bike and ran with unprecedented speed. It was a close call. Exhausted, we retired at the Snow Leopard hotel, and enjoyed a bonfire under the full moonlight. The next day, we ascended to the world’s highest desert, a sight we didn’t expect at the foothills of the Himalayas, and saw double hump camels and stunning sand dunes. We prepared for our main ascent and opted for some much needed rest and relaxation at the Sulfur springs.

ASCENDING THE HIGHEST ROAD:

5680 METERS

As excited as I was, an avalanche hindered our final momentous ride. Suddenly we were tight for time, yet I took this as an opportunity to bond with other locals making the same trip. Still, I was the only one on a bike, and I knew that I was running out of oxygen as the air thinned and we weren’t supposed to remain exposed to this high altitude that we were approaching for more than thirty minutes.

15 KM to the top, the roads were grueling, icy and I did everything I could to keep the bike from falling. I felt like I should head back, but I persevered. I decided that my wife should ride in the support van and I rode alone. The temperatures were dropping rapidly and as we went up, the oxygen levels decreased, but I refused to use the tanks. 4 KM away, at the last minute the snow from the avalanche was cleared and we ascended victoriously to the top. I was on top of the world, riding with the clouds and the birds by my side. We arrived at an altitude of 5680 meters, even higher than the mighty Everest’s base camp. My fear of heights disappeared, and I suddenly felt flying while my feet were still firmly planted on the ground. We rode through clouds, mountains, and towns. It was an epic journey indeed.

Throughout this entire trip, I kept the word Jullay, a Ladakhi word of positivity, on my mind. I kept hearing it, and I believed it. The locals associate the word everything positive. From “good morning” to “good night”, Jullay surrounded me despite the challenges. I liked this word so much that I decided to call the film Jullay.

I would like to extend special thanks to my friend and local Kuwaiti Director Hamad Al Sarraf who has volunteered to codirect and post produce the film making this journey a true collaboration. With our wealth of footage from this trip, and our experience in previously collaborating on the short film Viktor, Jullay still surrounds me, and I can still feel the good vibes.

For more information, follow Waleed Shaalan on Instagram @WaleedSha3lan and Snapchat @WaleedShaalan.