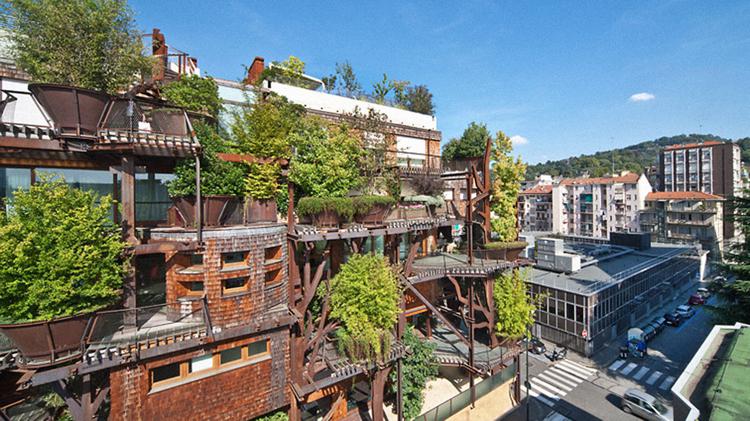

Walking down a certain city block in Turin, Italy, you won’t see any trees lining the sidewalk. Instead, they’re suspended in the air: A new five-story apartment building called 25 Verde is covered with 150 trees, each surrounded by custom-shaped terraces. It’s the apartment building version of a treehouse.

“If the trees are integrated in the building, they are closer to the people who live there, and so there is more integration between man and nature,” says architect Luciano Pia. The trees help filter pollution from traffic on busy nearby streets, absorbing around 200,000 liters of CO2 emissions every hour in one of Europe’s most polluted cities. As the seasons change, the leaves help shade the apartments or bring in warmth, creating a microclimate for the building.

While tree-covered buildings keep showing up in architectural renderings (you could argue that “put a tree on it” is the new “put a bird on it”), the new building in Turin might be proof of how an urban treehouse can actually work.

Unlike many conceptual designs, this isn’t a skyscraper, and that means the trees have a better chance at survival. “In tall buildings, the outdoor climate is considerably different from that on the lower floors to the ground level,” says Pia. “At the top there is always wind. I don’t think planting trees on skyscrapers is a way to go.”

In Pia’s design, each of the trees has room to grow. “You have to plant them in pots sufficiently large to ensure the nutrition and root growth,” he says. The building also surrounds a courtyard with another 50 trees, and has a green roof. Basically, when residents look outside, they’ll see a mini-forest instead of concrete.

Meanwhile, a few hours away at the University of the West of England, researchers are working on lights powered by an abundant resource – human pee. Inspired by the poor lighting conditions of refugee camps and the dangerous environment in which that places women, the team have developed fuel cells that are integrated to a toilet system. Inside are microbes that eat up urine and produce electricity as a by-product. It’s not a lot of power, but enough to run modern LED lights that are hyper-efficient. A single toilet could power a string of nearby lights, the team says.

Typically, camps today will use either batteries or diesel generators, neither of which are ideal. The batteries will run down after two or three years, while the generators require fuel supplies and maintenance. The fuel cell and LED approach could last 20 years and need little upkeep. Running off “microbial fuel cells,” they could light up off-grid camps and help keep refugees safer.

The bathroom is now being tested by students at the university (it sits outside the campus pub, so it’s getting plenty of use). If it proves durable enough, Oxfam hopes to test it at a camp in South Sudan and then start mass-manufacturing it as a kit.