Huascaran Sur (South) in the Cordillera Blanca of Peru, at 6768m is the highest peak in Peru and the 4th highest in the western hemisphere… a big mountain requiring 5 days to climb (provided you are acclimatized) and two high camps. This was my objective as I set off to South America on June 30.

But I also had another, more important, objective for this trip – to raise funds and awareness for the Children’s Cancer Center of Lebanon, the foremost cancer research and treatment facility in the Middle East. Nothing is more incredible than the joyful journey of childhood, where dreams are made, and hopefully fulfilled later in life. I consider myself fortunate to be able to pursue my passion for the mountains… but some of these children may not be so lucky; when we are robbed in our youth of the chance to live our life and our dreams, it is a sad moment. With the help of my corporate sponsor ARAMEX, I was hoping to make a small contribution to the formidable fight against this deadly disease. My deepest appreciation goes to them for their contribution.

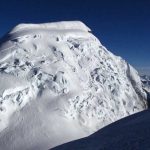

As I flew into Huaraz, the valley town from which our expedition would be based, I got my first glimpse of Huascaran – it was overwhelming… two peaks, straddled by a narrow ridge or col… a sheer mass of ice and snow dominating the horizon and the valley beneath. I would not characterize it as a pretty mountain; it looks like a massive bulge on the horizon, easily dwarfing the surrounding, more graceful peaks. But it was awesome to look at; you couldn’t help but fathom its brutal beauty and impact. To the Inca, it had been a holy mountain, and is still revered, and feared, by the locals. It is both a giver and a taker. In 1970, after a massive earthquake, a section of the north summit broke off and came hurtling down onto the village of Yungay far below – a sliding mass of ice, rock, mud, death, and destruction. At the end of it 25,000 lost their lives.

So here I was to climb this behemoth, with another climber, our two guides Ignacio and Willy, expedition cook Carlos, and 3 porters (Cirillo, Paolo, and Taylor). Our route would start at the village of Pashpa, altitude 3000m, and would consist of a base camp at 4700m and two high camps, at 5300m and 5900m. The route between the high camps (camp 1 to camp 2) is the most treacherous part of the climb as it snakes through what is known as the “canaleta” or canal – so called due to its narrow, winding shape, resembling a water canal – only vertical. Because of this constricted shape, the canaleta is an “ice fall” – everything falling from above funnels through it. Depending on conditions, it can be highly technical and onerous, requiring maneuvers through and over numerous crevasses, seracs (over-hanging ice cliffs), and ice walls. Once the ridge above the canaleta is reached, there is a 400 meter traverse through an avalanche zone before reaching the relative safety of the high camp on the col, known as the Garganta (throat in Spanish, again due to its shape). This is an unfriendly place at best – cold, windy, heavily crevassed, and on occasion prone to avalanches. But it does serve as the launching pad for the summit, a further 900 vertical meters above. The first half of this part of the climb is up a 45-55 degree slope, at places steepening to 60-70 degrees and requiring the use of ice tools. At approximately 6400m, the slope gives way to the summit dome, a gently rising, and endless, expanse of snow and ice. The decent is the reverse, through the same terrain.

I knew I would have many obstacles ahead of me, least of all the mountain itself. First there was the question of the altitude and the numerous ailments it can cause in the guise of acute mountain sickness (AMS) – should my body not acclimatize properly, it would mean the end of the expedition. Then there was the question of staying generally healthy, and in particular avoiding the debilitating stomach bugs expeditions are notorious for. Being in South America meant exposure to a host of new bacteria I would not be accustomed to. If I managed to surmount these health threats, would I be able to survive camp life – tucked into tiny tents with other climbers for two weeks – little if any privacy… no access to toilets or any of the other small and large comforts of life? Throw in the cold (-20C), howling winds, exhaustion, insomnia, and general discomfort and camp life becomes almost as challenging as the climb!

And of course there was the mountain itself and all that comes with it. Objective hazards – rock fall, avalanches, seracs breaking, bad weather – and real hazards, like falling or losing the route… all had to be reckoned with. I was aware at every moment of these lurking dangers – this was a mountain that had killed people in the past…

As with any high altitude peak, tackling the mountain head on is not possible. A program of acclimatization is necessary, both for safety and success. And so I had to spend nine days hiking and climbing other peaks before getting to Huascaran, the general rule being “climb high and sleep low”. This meant that as time wore on I would gradually gain higher and higher elevations getting my body accustomed to the change in pressure. But it also meant depleting precious energy before I even set foot on the mountain. Huascaran itself entails a strenuous approach and a total vertical gain of 3800m – no small feat at high altitude!

We set off on July 9 from the small town of Pashpa with its dusty roads and dilapidated buildings. After loading up the donkeys and our packs we headed up to base camp at 4700m. The path took us through the upper reaches of the village and its neatly cultivated fields, through a rolling eucalyptus plantation which then gave way to an indigenous forest of quenual trees, a magical place reminiscent of a fairy tale. Base Camp is a collection of cleared terraces overlooking the valley below. It is a pleasant place where the hustle and bustle of the climbing parties comes together, numerous tents set up in close proximity, donkeys foraging, porters going about their tasks and cooks in their mess tents creating all types of tantalizing aromas. It was a little luxury for a night, as the next day we set off for camp 1 on the glacier at 5300m. This route required scrambling up the glacier moraine over huge boulders polished smooth as the glacier retreated over hundreds or thousands of years. Small enchanting streams surrounded us and panoramas of the valley below abounded. We donned our crampons and roped up at 5000m, the start of the glacier. The sunlight reflecting off the ice and snow made it unbearably hot, and so layers of clothing came off… but each strong gust of wind reminded us of the altitude and sent shivers down our spine… literally.

At camp 1, we went about the business of setting up the tents and preparing the gear. Digging a flat surface on the sloping glacier at that altitude is hard work, but necessary to ensure a good night’s rest. You wouldn’t want to keep rolling down towards your tent companion. Once camp was set, Carlos got to work and soon we had a hot meal. But the best was yet to come for the spectacle of the descending sun was worthy of any tropical sunset on an island in the middle of the ocean – endless hues of crimson, orange, gold, and red – with fantastic cloud formations scattering and reflecting the light off the mountain and glacier. Everyone started in awe… it was energizing and uplifting, sending us off to our tents in good spirits. Inside the tent, we organized our packs for a 3am start, and finally crawled into our sleeping bags, with our hot water bottles providing what little warmth and comfort one could have in such a place. However, for me the pleasantness ended there for I was in the grip of high altitude insomnia and could not sleep a wink. By 3am, utterly exhausted, I made the decision not to continue. I offered to head back down to enable the rest of the party to move on, fully realizing that this would mean the end of the road for me… but we were a team, and given we had a couple of contingency days built into the itinerary, Ignacio decided that we would spend another day at camp 1 to further rest, eat, and acclimatize. This was a welcome lazy day on the glacier for me, a chance to recoup my energy, strength, and motivation.

That night, I slept like a baby, and by 5am we had packed up the entire camp, had a quick breakfast and headed for the canaleta. By the light of our headlamps we made our way through the crevasses and ice formations. It was steep but we had to move quickly to avoid any unpleasant surprises. Moving fast at that altitude is painful, like running a marathon uphill – each breath fails to deliver the required dose of oxygen, and so it was a struggle to maintain the pace… but necessary. A few sections were vertical requiring ice tools and protection. Under the cover of darkness, I could not really put the route in perspective, I just knew it was up, up, fast, fast. Once through the canaleta, we reached the ridge leading to camp 2 across the avalanche field. Here, we paused for a badly needed breather, as the light was just starting to break. I looked back and stared at the way we had come. Now I could see why this place was named “the canal” – it was just that. We were lucky this year in that conditions were excellent – this meant no hair-raising traverses of ice boulders, or having to circumnavigate huge yawning crevasses. For sure, we had made a few adrenalin-gushing jumps… but still manageable. I then looked ahead and could see the avalanche debris – huge blocks of blue ice as big as refrigerators. I closed my eyes and imagined the deadly outbursts of the mountain that had brought these here, and prayed that they would not happen in the next twenty minutes. Luckily the path was a gentle incline that eventually descended before reaching the Garganta, so it was not strenuous. Plus, it was still early enough that everything should be frozen solid. Nevertheless, we bolted across reaching the high col as daylight in its full splendor engulfed the mountain. The entire ordeal had taken us only two hours, where normally it would have taken three or four – but the good conditions and abilities of everyone on the team made this pace possible… thank God!

Camp 2 was like being on another planet. We shared what little space was available with a couple of other parties, and a number of huge gaping crevasses. Sheer Ice cliffs loomed over the entire col –they revealed a spectacular display of strata formed over thousands of years, each in a different shade of white, grey, or blue. At either end of the col towered one of the Huascaran giants, Norte on the left and Sur to the right – each a massive bulk of white. I wasn’t sure which one looked more beautiful, or unfriendly. It was hard to stare at them without a sense of amazement and wonder, tinged with terror. Again, we set up our tents, and amazingly an hour later I had another hot meal in my hands – Carlos was extraordinary. Boiling water at 6000m requires patience, diligence, and back-breaking work, yet he seemed to continually be melting snow for drinking, cooking, and washing. And his hard work paid off, not once did anyone on the trip get sick.

As darkness fell, it got bitterly cold, -20C, and the wind started to howl. I crawled into my tent and went to work by headlamp light preparing my gear for a 1am start. It was essential to travel light so I took only what I thought I absolutely needed. With everything in order I slipped into my warm sleeping bag and fell soundly asleep. Sometime later I was awakened by a strange noise which I soon realized was the wind madly gusting against the tent. My heart sank as I realized what it was… I knew we could not climb in such conditions. I couldn’t resist the urge to have a look, so I donned all my warm clothing and boots, agonizingly laborious tasks, and went outside. Sure enough the wind almost swept me off my feet. Despite this, I stood mesmerized by the incredible views all around me. The valley below was dark except for the shimmering lights of the little villages. I felt a tinge of envy at the people down there, sleeping in warm, safe, comfortable beds. The Garganta itself was a ghostly bluish-white, shimmering in an other-worldly way, and the Huascarans were like sleeping giants, alien in the light. Their slopes looked like the surface of the moon or some unknown planet in the farthest reaches of our galaxy. It was only when I gazed up that I realized where the light was coming from… the sky was studded with stars, millions upon millions… there was hardly space to fit any more; the swirling arms of the Milky Way added texture and depth, evoking a sense of mystery and distance. It was one of the most magnificent views I had ever seen. At that moment, I realized that I did not want to be down in the valley in a warm comfortable bed. I was happy being cold and miserable up here, witnessing such a spectacular display of the cosmos and mother nature.

I lay in my sleeping bag for the next couple of hours in a light sleep. Around midnight I looked at my watch and listened. It was eerily quiet. Was I imagining or had the wind died down? Ignacio’s call to get ready confirmed that this was no dream, the wind had completely abated, we were going for the summit! The spirits of the mountain were being kind. We quickly geared up, and by 1am we had roped up and made our way across the glacier above the col to the base of Huascaran Sur. We zigzagged our way up the mountain, an extreme power Stairmaster workout at 6000m at 1am! But the route was interesting and varied; we traversed across several ice faces, climbed up a few others, navigated around crevasses, and toiled up steep ice slopes. By 3:30am we had climbed the face and were approaching the summit dome. I knew we were approximately half way up the mountain by then which would have put us at about 6400m. It was difficult to breathe properly; there was no satisfaction in taking deep breaths either. The key was to find a pace, a rhythm, and focus on it, maintain it, and repeat it, over and over.

As we reached the summit ice field, we stopped for a brief break. I was acutely aware of the intensity of what I was doing, the sheer toughness of it. Why was I here? What drives people to such inhospitable places, places they are clearly not meant to go? This is the domain of rock, ice, snow, and mountain spirits… it wasn’t meant for us. I had no easy answers to these questions; what drives each person is different. But I do know that we all have one thing in common – a little voice inside of us, and when it calls strongly enough, you have to listen. To ignore it would mean denying yourself the chance to explore the world, and more importantly, your inner self.

With those thoughts for company, I set forth for the summit. If I had thought it was difficult before, it became agonizing. The altitude took over; it ruled you, controlled you. Your body, your thoughts, and your spirit became subservient to it. The rhythm… breath, step, breath, step, pause—breath, step, breath, step, pause… you couldn’t break it; to lose it would mean losing focus – and losing focus was dangerous, it meant other thoughts would creep into your mind… thoughts of giving up, retreating, or just collapsing. So you focus on the rhythm and on the summit and you keep going, one small step after the other, battling your demons, in pitch darkness. And so it was for the next couple of hours. As we neared the crest of each ridge I found myself praying that it would be the summit, yet another ridge would appear on the horizon, further up. Not there yet! Must keep going!

As the darkness started to give way to the break of light we approached the crest of one ridge. It appeared more massive than the others, and there was nothing beyond it. We stopped dead in our tracks…. the summit! First light, perfect timing! And so it was the final approach at dawn. Each minute brought a different hue, spectacular colors reflecting off the ice and sky… the horizon a sliver of deep burning orange radiating the myriad hues and shades of a magnificent sunrise. We were above all the other peaks, in fact, we were towering over them. Peaks which were mighty in their own right appeared as little feeble ridges far below. Such was the mass of Huascaran that it dwarfs all else.

A few more steps and we were there, 6768m! We had made it! It was 6:10am. We hugged and congratulated each other, relishing the moment, rushing from one incredible vista to the other, exploring every view and imprinting it upon our memories, and cameras. It was bitterly cold, but still no wind… how lucky we were. I had to keep flailing and beating my hands to keep them warm, but I didn’t care (the numbness in them didn’t subside till four weeks later!); I had been engulfed by an intoxicating euphoria, a flood of adrenalin, a cocktail of emotions. I stared at the panorama of peaks around me, delicately colored by the masterful hand of the rising sun. I was exhilarated, and never had I felt so alive. How strange that only the prospect of a possible death can unleash such a powerful feeling of life…

After about twenty minutes, we donned our backpacks and headed back down. At this point, the number one objective becomes to get off the mountain safely, and so the descent was swift; we were back at camp 2 in only two hours, the entire climb having taken seven hours whereas the usual time is 10-12. In the daylight I was able to see the route… it put the size of the mountain in perspective. We had climbed over towering seracs and ice walls, and crossed massive snowy slopes that fell straight to the glacier below. We had traversed vertical ice cliffs on a path half a foot wide with nothing beneath, sheer drop-offs. The crevasses were wide and deep, gnarled and twisted. And yet it was all ruggedly beautiful and inspiring.

At camp 2 I collapsed inside my tent, still wearing my boots. Since we had made such good time, we decided to head back down all the way to base camp. It was still early enough for us to deem the canaleta passable, and we retraced our steps across the avalanche field and down the winding slopes of “the canal”. Again the daylight offered the details of the route. It was an unearthly place with fantastic ice formations, deep chasms, and wild crevasses. I felt so relieved that we were revisiting it descending rather than ascending!

I did not breathe a sigh of relief nor celebration until I was off the glacier… I had made it! All the agony and doubts quickly melted away, and I could feel the lure of the mountains tugging at me again. I looked back with a tinge of sadness. This mountain had held sway over me for five days. It had been my life; it had shaped my thinking, outlook, thoughts, and emotions. I felt somehow connected to it, and still feel this way to this day. I immediately knew that I was, and have always been, afflicted with “mountain madness”! No other experience can rival the sheer complexity that defines the relationship between man and mountain.

Back to civilization, I made the best discovery of all… the expedition had raised $13,000 for the Children’s Cancer Center of Lebanon!! My deepest appreciation and thanks to all who contributed.

If you would like to make a direct donation to CCCL by using your credit card, please go to: www.cccl.org.lb/donate/index.htm Under “Donation is related to”, please tick “Support Henry Saliba’s climbing expeditionin the Andes of Peru”