“Will you have to wear the black sheet thing?” was often the first question I was asked when telling people about moving to Kuwait. Then my political activist friends would ask indignantly, “How can a feminist go to Kuwait?” My pub buds would state, “It is a dry country.” To which I would nod in agreement but think to myself, “Of course it is, it’s a desert!” I had never even heard the term “dry” before 2012. Unless it was used to order a pinot grigio during girl talk, which was rare because I only had one girlfriend, finding it hard to relate to women outside of politics, preferring the company of men.

Having been on the front lines arguing about how the nuances of experience with regard to intersectionality and feminism should inform National Union policy, it was odd to consider moving to a country where the only thing I knew about women in Kuwait was that they had to cover up.

And I didn’t really hold much respect for women who could be told what to do, think, and wear by men, conveniently ignoring the patriarchy that informs all our own mores and laws in the West. I barely knew anything about Kuwait, what I did know came from living in the United States during Desert Storm, so, practically nothing.

Having, as a child, kept my nose in books that told of the brilliant and quick-witted Scheherazade’s tales of The One Thousand and One Nights I also had this romanticized idea in the back of my mind, of Middle-Eastern women as dark mysterious creatures who could control men with a just a bat of their lashes. I also had seen a documentary by a British, Asian, Muslim female journalist, about what goes on under the abayas of women in Dubai. Clad in Chanel, accessorized by Hermès, dripping in diamonds and beautifully made up, with lashes added to the fullest.

Armed with my suitcase filled with floor-length skirts, long sleeved tops and a satin abaya borrowed from an aunt who’d lived in Egypt back in the eighties, I arrived in Kuwait not knowing which of the tropes was truest. Instead, I encountered women the likes of which I’d never met before nor even imagined meeting, especially in this location.

Working in luxury fashion I expected to deal with women who were high-end sartorialists, but outside of the store there were myriad women expressing themselves through bold fashion choices and very few of them were covered, although dressed modestly. I had never seen quite so many exquisitely made up women, all masters of the symmetrical, winged eyeliner.

The women who were covered also were magazine-cover ready, and I found myself staring at how talented they were at applying the mask of maquillage. The only other time I’d lived in a country where local women were clearly making an effort to present themselves so immaculately was in hot-blooded Colombia, and this included women from within all socio-economic backgrounds.

As I was seeing most of these women in malls, where people would pointedly come to promenade, I must have been seeing a slightly skewed aesthetic of the very best face of these women, surely. Then I went to a local farmers’ market and was blown out of the water. No wellies and wax jackets here, but loads of Givenchy, and even more Chanel.

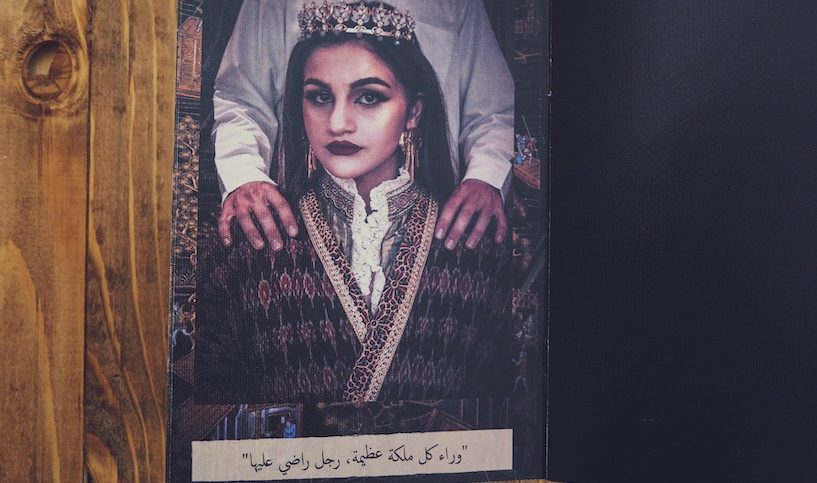

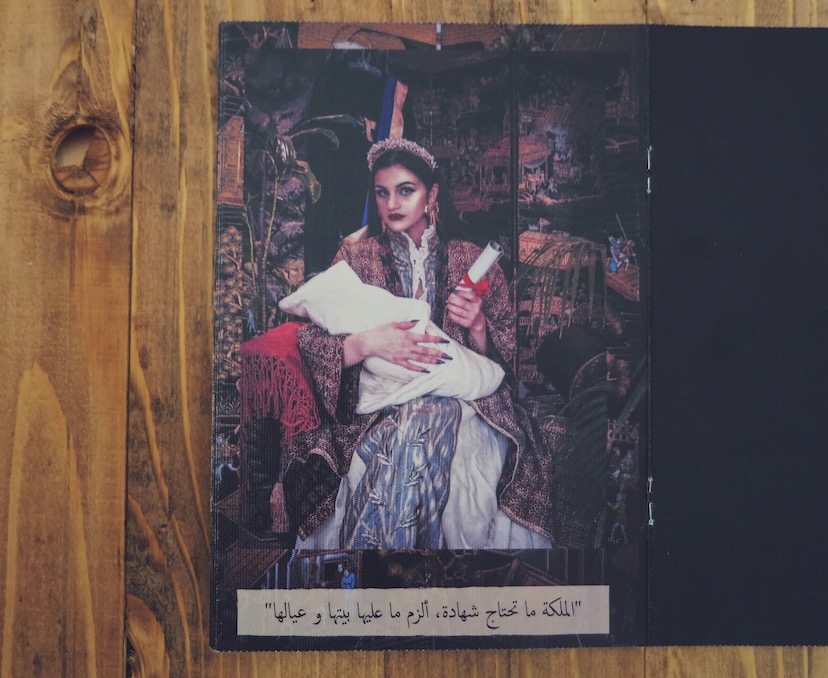

Women with access to money who weren’t afraid to conspicuously spend it, with attitudes more like queens than princesses. “Heavy-weight diamond champions” is a phrase used by artist and creative Xeina Al Mussallam. But then I got talking to the market vendors and the organizers and started meeting examples of women who were impressive for completely different reasons.

These were entrepreneurs, and young women event planners with a goal to change perceptions in Kuwait on eating organic foods, trying vegetarianism and not using plastic bags. Seven years ago, this was revolutionary in Kuwait. I also met women with high-flying full-time jobs who had their own side hustle of selling crafts or baking cupcakes and selling these at markets and fairs that were organized again by local women.

There were even super-luxe markets where the products included precious stones jewelry, but for body piercings. A whole new economy burst on to the scene championed by women, and now we can enjoy markets nearly every weekend during the cooler months.

There has even been an impact on legislation with Kuwaiti home businesses being granted licenses, and Kuwaiti women are demanding that expat women be also granted this same privilege, recognizing that this move would be empowering and liberating, particularly for women with little or no income. Other legislative changes are being campaigned for and spearheaded by women regarding domestic violence, equality of the sexes, and human rights.

Within the Arts there are women here at the forefront launching businesses focused on art and creativity, giving back to the community, employing like-minded people in these projects and sharing work with local galleries and nationally owned performance venues from the Dar Al Athar al Islamiyyah to Sheikh Jaber Al Ahmad Cultural Centre (JACC) boosting the reputation of Kuwait internationally when it comes to music and theatre. Writing of JACC, some of the most iconic buildings and chalets in Kuwait have been designed by female interior architects.

Female students are studying abroad and coming back, influencing and driving further change year after year. So many women I’ve met have MBA’s or PhDs, and are impressively highly educated.

While these privileged women are not typical of all women in Kuwait, it is noteworthy that so many women in such a small local population are doing things that are surprising, given how the West is told by media of the horrifically oppressed Middle Eastern woman.

In my experience young women are using the abaya and hijab in ways that men probably hadn’t considered. They say it gives them freedom from judgment as they are not criticized by elders, and freedom of movement because they are not watched closely.

In actual fact, these young women are most likely living more liberally than one would have guessed just by looking at them. Other young women are just outright rejecting what they feel are anachronistic assumptions of a woman’s role in Arab society. Discussing this role-rejection with them, you can tell it is not so easy to throw off the shackles of others’ expectations. This is especially true if you are struggling to juxtapose filial piety and searching for something more for yourself, and believing that wanting something different than what has previously been the norm, is not haram.

In short, there isn’t enough room here to say that the women in Kuwait rock, and I am now no longer surprised at how in awe I am of yet another woman here whom I’ve recently met socially, interviewed or worked with. These women have become successful by themselves for themselves, although sometimes Xeina says it is rare for this success to not be attributed to someone else; the husband who has allowed his wife this accomplishment for example. A belittling concept.

No wonder then, that there are vibrant, educated and thoughtful women railing against it. And so, in Kuwait and totally opposite to my preconceived ideas, my social circle of female friends has increased although the chat is now over a coffee, and not something stronger.

Incidentally it’s at Richard’s Coffee Bar that a bazaarite first saw the arresting images within the booklet “The Queen”, also conceived and created by Xeina, and brought the art publication to the office.

This sparked lots of conversation around women in Kuwait, and how many incredible examples of women we see as mentors that we can each cite. Unfortunately, it’s men I’m less impressed with here, they can’t seem to do much for themselves at all, but that’s a whole other story.

For more on Xeina Al Musallam’s project, “The Queen” visit www.soundcloud.com/almusallamxeina.