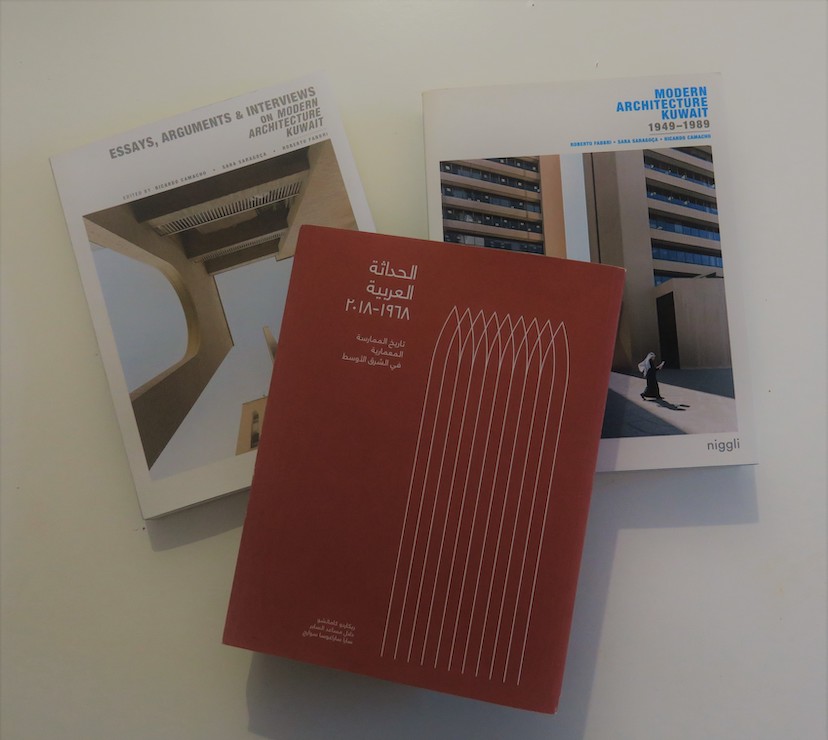

It has been 5 years since the book “Modern Architecture Kuwait 1949–1989” was published, a collaboration between Portuguese architect couple Ricardo Camacho and Sara Saragoça Soares and Italian architect Roberto Fabbri. It was a first of its kind systematic analysis of modern architecture in Kuwait documenting the dramatic transformation of Kuwait City with the start of the oil boom. It was followed by “Essays, Arguments & Interviews on Modern Architecture Kuwait” featuring interviews, essays and arguments by local and international scholars. Earlier this year the couple’s third collaboration was published “Pan-Arab Modernism 1968-2018: The History of Architectural Practice in The Middle East”, co-edited with Kuwaiti architect and researcher Dalal Musaed Al Sayer.

In the introduction to their first book, they wrote their intention was to write “a practical tool that would trigger better use of these buildings”. Since its publication many of the buildings that were documented in those books have now been demolished or are in states of disrepair. However, their work has come at a time when there is a growing interest among young Kuwaitis in conservation. The new book documents how modern Kuwait was built in the utopian spirit of pan Arabism.

bazaar’s contributor Reem Al Gharabally spoke to the couple from their home in Portugal over Zoom about their years working in Kuwait and what inspired them to embark on such a monumental task.

What bought you to Kuwait?

Ricardo: I had a colleague in the US from Harvard who was from Kuwait, Abdullatif Al Mishari. We did a trip around the world, a kind of interrail but by plane [laughs]. When we were in Mumbai we decided to go through Dubai and Kuwait. That was first time I came to Kuwait in October 2009. After that first trip we started engaging in different projects and I found myself spending more and more time here until finally in 2010 I moved here. The way we moved to Kuwait was more organic and not so professionally or financially based.

Sara: I started moving back and forth from Portugal and Kuwait from 2010 and the rest of the family moved in 2012. At the time I was doing my Masters theses in Portugal about preservation. I was thinking of doing something about Portugal, but I was travelling back and forth between Portugal and Kuwait and I saw all these buildings here.

I remember visiting Sawaber in Ramadan, August 2010 and it was really hot. It was such an interesting experience. After that summer I proposed to write my thesis about Kuwait. So, when Ricardo suggested moving to Kuwait it was very easy for me to say yes. I already knew the country and it felt very familiar.

How did the idea of the book come up – to make a catalogue of these modernist buildings?

Ricardo: The intention was to use books or exhibitions as a way to stop the erosion and demolition of this heritage. There was a sort of a momentum in the beginning of the 2010s where we felt there was a growing interest in preserving these buildings and we were supported by Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Science (KFAS) and Dar Al Athar Al-Islamiyah (DAI).

Sara: Since the old mud town was demolished, these buildings were the old buildings now. When I was researching the book, I never thought that so many would be demolished in such a short period of time. The former Gulf bank headquarters was demolished 3 days after the book launch.

Ricardo: At the same time, we were involved in the construction site of Shaheed park and we were exposed to a larger network, that were part of the construction site in the past. This was also very resourceful. Until that point we only met younger people.

Sara: 2013 was a very busy year in a good way. We were in Shaheed park working there, getting involved in the research. We were really engaging in the country. I remember feeling very happy that year in Kuwait.

The book reads like a labor of love. Being from Portugal did you feel some sort of affinity to Kuwait?

Ricardo: I felt attached to Kuwait apart from that city was the rurality in the way older Kuwaitis carried the past. I am not saying this in a depreciative way. I am saying this in a very culturally engaged way with the territory, with the landscape, the dates, the palms, with the farms in Abdali and Wafra, the coastal line, the relation with the beach. All this was for me was stronger than the desert and a post oil town built in the desert.

Sara: We did not move to Kuwait for financial reasons. We were in Kuwait like we were here in Portugal. For us it was like the same thing. We were developing our interests in Kuwait and we met a lot of amazing people that allowed us to feel at home.

The introduction to the first book says the intention was “to create practical tool that would trigger better use of these buildings”. But since its publication some of these notable buildings have now been demolished. Do you think the book can still fulfil its aim?

Ricardo: The book wanted to engage the younger community of professionals – architects and engineers – so when they are approached by a developer and clients, to consider preserving the existing condition rather than demolishing.

Sara: I remember going inside the old Chamber of Commerce with a few architects just before it was demolished to take pictures. I was shocked because for me the building was not only a nice building, but it was also very solid. I think it was important for young local architects to realize that these demolitions were happening in a way that should have been stopped.

Why is it important to have a heritage program?

Ricardo: There are certain spaces, certain buildings that preserve a certain mystery, a freshness. Those spaces are worth preserving. Not because they represent a nostalgia of a particular moment but because they keep that feeling throughout time and this is very important to recognize these are the spaces that build the urban quality of a city.

Sara: When you are in such a harsh environment with high temperatures it is important to preserve spaces where you can breathe a little, where you can walk. You don’t have that with skyscrapers or a fancy lobby full of security.

What would you say to young architects interested in conservation?

Sara: I hope they will keep those dreams and those ambitions alive. Otherwise, everything will disappear. It will be impossible to stop it. Because it sometimes happens when you have the chance to make a profit you forget your original dreams.

How is the third book different from the first two books?

Ricardo: The book was sponsored by PACE and their archives influenced the structure of the book. Even the years 1968 to 2018 represents the 50 years of PACE. Of course, a very important person here along with Tareq Shuaib who made the PACE archives accessible to us, is Dalal al Sayer, the co-author. Dalal has a very strong interest bound with her PhD research on the post oil influence and the idea of the network of countries and cities around the region. The previous books were done by foreigners. It was missing that strong link to a truly local agenda that Dalal’s brings to this project.

Sara: And it is a bilingual book and that is a statement in itself. It is a local Arabic book. It is not a book by foreigners talking about Kuwait. Ricardo: I would also mention a person who passed away recently – Charles Haddad. A former partner and co-founder of PACE, a Syrian Palestinian in the diaspora that went to Lebanon and came walking to Kuwait in 1956. The interviews we had with him were fundamental.

You talked about a theory that Kuwait was built in a spirit of Mediterranean cosmopolitanism. Can you tell us more about that?

Ricardo: The idea was to cover the energy that flowed from the Levant into the Gulf, which is the true spirit of the Pan Arab – the migration of people but also the acceptation of bringing the cosmopolitanism and the urbanity of the Mediterranean into the Gulf. That is something that Kuwait lost somewhere on the way. That idea that your modern vison of a town was based on multiculturalism of the Mediterranean, on Cairo, Alexandria and Beirut. It is not the Dubai model that envisions an Asiatic concept of the new world, an American vision of the new world. The book tries to capture that.

There is a very small story in the book about the first graduates of the diploma studio at the American University of Beirut for architect and engineers in 1952. Their diploma project was on the Pan Arab highway which was the hope to freely drive from Beirut to Kuwait crossing Syria and North Jordan. It is a whole generation that did their diploma project on this idea. Some of them proposed motels, some of them a gas station. Charles Haddad proposed a Bedouin refugee town in the Jordan desert, south of Damascus. A whole generation was engaged with this Pan Arab spirit. These were the people who came here with hopes that Kuwait was part of the Middle East and not just a city in a new country.

Many times, there is this discussion about the legitimacy of a building that was designed by a foreigner in Kuwait to be a Kuwaiti thing or not. When you put that doubt you don’t understand what Kuwait really is. The buildings in the 1960s and 70s in Kuwait are the product of a multitude of people. The designer is a small fragment of what that enterprise represented.

For more information and inspiration follow @caamacho and @sarass on Instagram. To purchase the books, please check out these links: Modern Architecture Kuwait, Modern Architecture Kuwait Vol 2 and Pan Arab Modernism 1968.