By Jennifer Miller

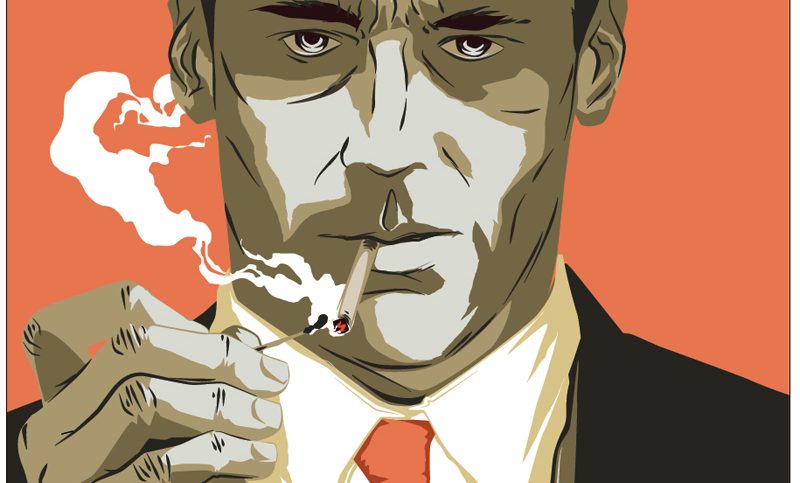

We’ll forgive Dexter a little serial killing. But what about Don Draper?

For years we’ve tuned into Breaking Bad, Homeland, or Dexter and watched really horrendous things happen. Blood splatters as Dexter plunges his knife. Walter White hacks up bodies and cooks meth. And Nicholas Brody plots to blow up himself along with half the U.S. government. But, as these shows’ long-term success suggests, we like these guys.

They may not be aspirational, but we’re rooting for them. We kind of, maybe, understand why they’re so damn angry and violent. And this makes all of their plotting and killing seem, well, not so bad.

A new study from the University of Colorado conducted by Maja Krakowiak and Mina Tsay-Vogel, explains why. What Makes Characters’ Bad Behavior Acceptable? The Effects of Character Motivation and Outcome on Perceptions, Character Liking, and Moral Disengagement, was published this March in Mass Communication and Society. It’s a mouthful, but it boils down to this: When we sympathize with a character’s motivations for committing a heinous act, we’re likely to excuse that character’s actions.

Obviously, this doesn’t always work in the real world. That’s because of moral disengagement: what the authors call our ability to suspend disbelief in the realm of entertainment. It’s the psychological reason we can keep watching all this stuff without feeling utterly disgusted.

But shows today are much more concerned with the morally ambiguous hero (or antihero) than they used to be. “Superman is clearly a hero and Darth Vader is clearly a villain,” says Tsay-Vogel. “But morally ambiguous characters fall into both camps simultaneously.”

In the study, Tsay-Vogel and Krakowiak had participants read a story about two mountain climbers, Craig and John. At a certain point, John becomes ill and Craig abandons him on the mountain. In one version of the story, Craig leaves his friend to help another group of climbers in trouble. In another version, Craig leaves because he’s so eager to reach the top of the mountain. In some versions of the story, John dies; in others he lives.

“We discovered that motivation played a bigger role than outcome in terms of how the reader felt about Craig,” says Tsay-Vogel. In other words, it doesn’t really matter whether John lives or dies, as long as Craig’s motivation for leaving him is altruistic instead of selfish.

And that’s why we sympathize with Dexter, who only kills other killers, and Walter White, who is trying to provide for his family. Similarly, Nicholas Brody feels that the U.S. government is refusing to take responsibility for the innocent children who died in drone strikes.

The theory doesn’t seem to hold up though with a character like Mad Men’s Don Draper. Don never (directly) kills anyone, outside of a fever dream; his actions are less morally despicable than Walt’s and Dexter’s. Notwithstanding the dual identity wrinkle, Don is bad in more identifiable ways–cheating, dissembling. But his motivations aren’t always clear, and certainly not always selfless. So…do we like him? Or does he just look so good in a suit we overlook his foibles? “If a character isn’t predictable, we have to reevaluate the character each time,” says Tsay-Vogel. “Someone who is inconsistently morally ambiguous could be seen as more evil because their intentions can change.”

Tsay-Vogel is currently working on a study that looks at Harry Potter characters to explore the continuum of moral ambiguity, including characters with shifting intentions. They’re also looking to see how genre affects our perception. They’re particularly interested in reality television, which is a bizarre simulacrum of real life. Does moral disengagement work in reality TV? Tsay-Vogel doesn’t know for sure. She can only attest to how much we love reality show villains. “It makes for really good television,” she says.