Steve McQueen was already a Turner Prize-winning artist when he made his acclaimed first film, Hunger, and he has only gone from strength to strength since then with Shame and 12 Years A Slave, which won the Academy Award for Best Picture. But after taking the Oscar, the London-born, Amsterdam-based director proved he still had the capacity to shock. The film world was stunned when he announced that his follow-up would be Widows, adapted from a hit 1983 TV series by Lynda LaPlante (Prime Suspect). It might have been the last thing anyone expected from the auteur, but look closer and it makes perfect sense. McQueen co-wrote the script with Gillian Flynn (Gone Girl), relocating the action to Chicago, and conceived a film that combines a heightened crime story with an intensely realistic world.

The story concerns a group of Chicago women who are left in dire straits after their career criminal husbands are killed in the course of a job gone wrong. The quartet needs a large amount of cash, and quickly, so their leader Veronica (Viola Davis, Fences) decides that they should carry out her husband’s next planned job to get the money they need. Small business owner and mother-of-two Linda (Michelle Rodriguez, Avatar) and the much-abused Alice (Elizabeth Debicki, The Great Gatsby) agree, recruiting babysitter Belle (Tony winner Cynthia Erivo) as the group’s final member. But in a town filled with corrupt politicians and formidable men, these women will have to struggle to survive the attempt, never mind to carry off the heist.

The film also stars Liam Neeson, Colin Farrell, Robert Duvall, Daniel Kaluuya and Jon Bernthal. That Chicago crime story might seem like a world away from the concerns of McQueen, but in fact, this is an intensely personal film for the director, who was swept up in the original show and has not forgotten it in the 35 years since. He explains why Widows was the film he had to make next.

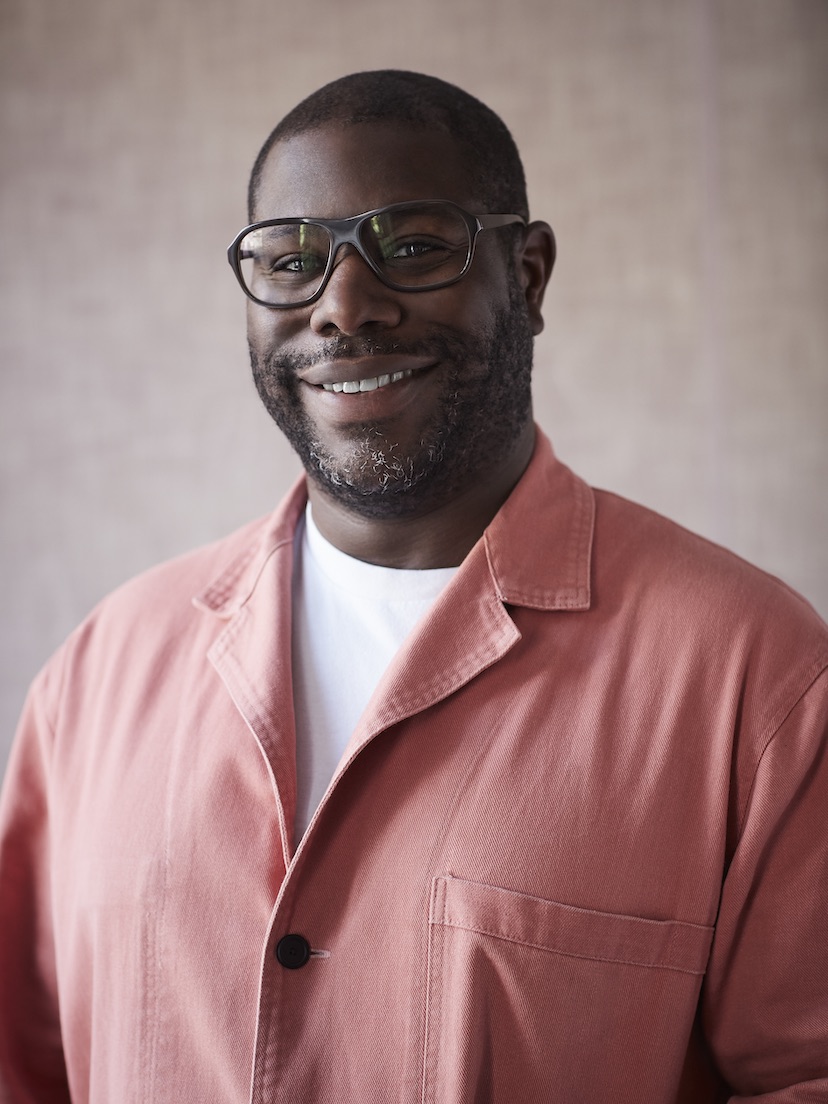

Steve McQueen. Producer, director and co-screenwriter of Twentieth Century Fox’s Widows. Image courtesy of Twentieth Century Fox

How long did it take you, after 12 Years A Slave and the Oscar excitement that followed it, to settle on Widows as your next film?

A: I knew that was going to be the next feature film, for sure, even during the prepping of 12 Years. I was 13 years old when I saw Widows for the first time on TV, and it just made such a huge impression on me. I identified with these women who were perceived to be not capable, and all they were judged on was their appearance. I identified with that, in a way. These underdogs were looked upon as nothing more than people who took up space rather people than who had anything to say or anything to contribute. And as a 13-year-old black child in London at that time, I resonated with them. These underdogs who eventually achieved something were inspiring characters, these four women.

So how did you actively begin work? Was the first step bringing in Gillian Flynn, who co-wrote the script?

A: I was already developing things when Gillian came into the creation, and she was just amazing. She’s a great colleague and collaborator and partner. We’re each as tough as the other, so that was great, having a person to throw things at and for things to be thrown at me. We were grappling and coming up with ideas. It wasn’t a case of what this person could provide and what the other person would provide; it was actually, have we got some kind of synergy? And we did.

Did you talk to Lynda LaPlante, who created the original series, as well?

A: I did, I did. The funny thing about Lynda LaPlante is that I met her at Buckingham Palace – as you do! There was an event for the Queen, and then some of us were taken for a sort of private audience with the Queen, and she was in the line-up. I asked her, “What happened to that project called Widows?” That was in 2014.

So it took another three years from that point before you were shooting in Chicago.

A: Yes. I knew I wanted it. The idea popped into my head in 2011, after Shame, because I was in Hollywood and it was a situation with all these actors I knew, who were around but weren’t working. I thought, wow. OK, you’ve been carrying this for 35 years, this TV program, but you had no idea you were going to be a filmmaker. You had no idea this would be a film you wanted to make. But then it obviously was a big idea and I thought, OK, this could be a possibility, and that was in 2011. So I started going to Chicago, talking to people like the FBI, former members of the criminal world, politicians, pastors. What was interesting about transporting the story from London in 1983 to Chicago in the present day, was that Chicago is a heightened city of now. Politically, racially, in all kinds of aspects. That was, for me, the place to stick it. This story is highly fictional, but I wanted to steep this fiction in reality.

Did you look to any other heist movies or crime novels for inspiration?

A: No. Chicago. Chicago was my inspiration.

You added a political race to the story, which I guess replaced the more police-driven elements of the TV show. Why was that important?

A: Well, what’s interesting is there are no police in my picture. The police are complicit within the system of the city. I loved that idea. But it [the political element] wasn’t instead of that; it’s how we live now. I wanted to bring our reality, or the reality of Chicago, within that plot. How people live! How we live, and how we try to access our way through the quagmire of a world we are given, and that we do have possibilities to change it. Sometimes we feel so paralyzed by the world we live in that we don’t have a handle on it, but I think somehow we do. If it rains, at least you can choose the color of your raincoat. Even that is an actual decision. You’re grasping something in your hands.

Given the importance of Chicago, what was shooting there like? You’ve avoided all the usual touristy establishing shots but still made use of the city’s incredible architecture.

A: In the movie, you have the landmarks of the every day, how people actually live. You have a situation where you’re dealing with where Belle [Cynthia Erivo] lives, and that project [housing estate], which is a notorious project in Chicago. When I was working there, they were erecting these 10′ fences around the project, and it was heart-breaking. When we went for the first time it wasn’t there, and when we went back to do another recce they were erecting these 10′ fences around the projects because they wanted to almost keep people in; these kids were screaming and running around, making all these wonderful kid noises on a summer’s day, and it felt they were being penned in. It felt like the obvious in some ways, it felt like a familiar story. So it was heavy.

Then, going from there to Mies Van Der Rohe’s home in the last building he designed [which played Veronica’s apartment], that’s within 15 minutes’ drive. You go from the poorest of the poor to that. We also saw a very notorious project that was knocked down and people were rehoused in hotels. These spaces are not meant for people to spend a long term in, but people have never been relocated elsewhere. You saw the poverty and the wealth within minutes. So it’s a different side, the real Chicago. In some ways, that tourist aspect of Chicago is like an amnesia. It’s almost like the carpet, things have been swept underneath it. There are two worlds. One, with gun crime in Chicago and whatnot, and the notorious policing. But if you want Disneyland, it’s there in abundance.

In terms of the question of gun crime and corrupt policing, it feels like that is what Chicago has been most known for in recent years.

A: One guy was shot 16 times in the back.

And that all informs the film; it’s built up around your characters. How easy was it to create that world once you got there and started talking to experts?

A: It’s really organic. If you take a character like Jatemme [Daniel Kaluuya], who is so steeped in violence he’s numb to it, in some ways his engagement becomes perverse because he’s so bored of it. The first thing you see of him, with those two gentlemen he shoots one and the guy is paralyzed. In the third situation, you see him, he’s so numb to violence that he doesn’t participate; he just watches TV. So that is a reflection of how violence has affected so many people in Chicago.

Let’s talk about the Widows themselves. You’ve located them all in different socio-economic layers. How long did it take to get them all situated in their respective worlds?

A: Yeah, it was long. It was long because again, the characters have to be believable. I think Belle was the first one, that was Cynthia Erivo. As far as Veronica was concerned, I didn’t know what race she would be – if she’d be Latino, black, white, I didn’t know. I had to figure that one out. And then Viola was the person. So again, she for me fits the Katharine Hepburn, Bette Davis, Joan Crawford mould. Greta Garbo! She has this gravitas, like those movies that were made in the ’30s, ’40s, ’50s and were the norm, but now apparently it’s weird that these people can carry major, epic pictures. I thought, that’s great, OK, Viola.

With Elizabeth, that again was a journey in how this Polish-American girl had been abused by her mother and her husband in some ways and not been deemed clever, just been used, and that was how that developed. With Michelle Rodriguez, she – interestingly enough – thought of her mother, got her involved into it. It’s interesting because Michelle said no to me at first. So then I had to audition other women, over 100 of them, and I couldn’t find anyone. I had to go back to her and say, please, can I please meet you? She said yes, OK, and we got on like a house on fire.

Tell me about the score. Hans Zimmer is known for these huge special-effects blockbusters these days, so was it the chance to do something different that attracted him?

A: I think it was a mixture of the narrative and me, and also pushing himself in a way. Sometimes, he’s gotten so big, he just wants to get back to him. It was him doing the music and only him. Again, I was sitting there with him, and there was a bit of sweat. He’s moved to London and it wasn’t a situation of giving this to that person, that to that. So that was getting into personal stuff as well. I loved the pieces he did, it’s a wonderful score.

I should ask about the men in the cast as well. Even for fairly small roles, you cast great actors like Liam Neeson or Jon Bernthal; is that to give your stars something weighty to react to?

A: It’s all about the women. All about the women! When in doubt, go back to the women. So if we’re stuck making the film, maybe in the cutting room, go back to the women. So yes, we gotta give them [the men] depth and purpose. Even if it’s a small role, they’ve got to be like icebergs. Even if it’s a small role you have to sense this huge mass below. I think we’ve done that, I hope we’ve achieved that.

The cast obviously bonded on set; did you expect that?

A: I think I have to give a shout-out to Michelle. I think Michelle Rodriguez was a big part of that. She was the glue. She’s social, so eclectic. It was wonderful, one of those things where she’s the life of the party so she made that clique. Michelle was DJ’ing between scenes. I remember them shouting, ‘She didn’t say that!’; ‘She did…’. It was wonderful, couldn’t have been better.

Was it a happy set overall?

A: It was. When everyone on the set is treated with respect, it’s so wonderful because everyone knows it’s their movie. It’s our movie. I think actors are very sensitive to their environment, and that when they feel they are in a safe environment they go the extra mile. They feel safe to play and make mistakes.

Was there anything that was new and difficult about the shoot? This isn’t an action movie but there are action scenes and some directors find those challenging or frustrating.

A: I had some of the best people in the business, and what was interesting was how I could work with them and make it exciting for them. ‘Oh, I never thought about that, OK, let’s try that’. When you’re working with people who have done it a thousand times, if you can bring something to them you see them think and then get excited about what they do again, that was great.

It wasn’t necessarily challenging; it was new. But new is exciting! I love being in a situation where you don’t know because then you learn more, and that’s just wonderful. Again, if I don’t have the answers and someone else does, then I learn so it’s wonderful. It’s being free enough to listen to people. Not enough people listen.

What was the biggest surprise in the course of making the movie?

A: The thing that made me happy was that people were great, as a team. I think that’s what it was. I think what this film is, it’s about a situation where there are so many people these days talking about [living in] a bubble. This bubble, that bubble. And it’s when people break those bubbles…

The fact that I’ve done a genre picture, as such; the fact that we’ve taken genre fiction and steeped it in reality so that everyone can be included, invited to this film, is very powerful for me. Similarly, these four women that come together from different races, different classes, and come together to do something, I think it’s indicative of what’s going on right now in the world. We have to break down these bubbles and embrace [everyone]. And it’s not about dumbing down to a lower standard; it’s about how do you introduce people into the narrative? If people go along and see a movie and eat popcorn and get introduced to or enlightened about this or the other, then fantastic. As well as have a great ride! Bob’s your uncle. I think you can have your cake and eat it too. I think you can have everything you want, and this for me is an extremely personal picture.

Photography by John Russo. This interview is exclusive to bazaar publishing in Kuwait and is courtesy of 20th Century Fox Middle East, @20CenturyFoxMe on Instagram.