The group of art students and their professor piled into Aseel AlYaqoub’s studio at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York to critique progress on her latest piece, Mother Tongue. At the center of the room on a table sat a layered world map. On the wall hung her art statements in 70 different languages, none of them English. Her multilingual colleagues immediately searched for the statement in their foreign tongue. For a few moments those who only spoke in English attempted to garner as much information as they could from the others, but felt very much left out.

“I’m a product of globalization and it’s been my focal interest to look into what that means,” she told bazaar. “Mother Tongue explores language and how it is such a pervasive component of our every day lives.”

For AlYaqoub, the art she produces allows people to experience what it means to be an outsider in your own environment, whether at home or abroad. She wanted her English-speaking colleagues to feel out of place, and realize that the Western world is not the whole world.

AlYaqoub, a native Kuwaiti, moved to London at 17 to study Architecture and Spatial Design. Six years later she returned home to a country that was very much changed. With the help of Teddy B. a teddy bear that served as her alter ego, she created a photo blog experiment aimed to rediscover her country.

“The bear was acting as a social buffer between me and society to allow myself to explore my own country through it,” she said. “[It] was purely symbolic of a universal object, an object that most of the world can relate to and one that can create multiple reactions both in the physical and viral sense.”

One year, and 365 photos later, AlYaqoub came out as the blogger behind the posts in her first exhibition at the Sultan Gallery. The experience was supposed to help her reintegrate herself into her own culture, but instead accented a misplaced individuality in an exclusive society.

“We use our nationality as a common dominator and hope we all share similar ideologies, but obviously we don’t. I’ve given up working as a collective and find it best to contribute individually the best way you see fit.”

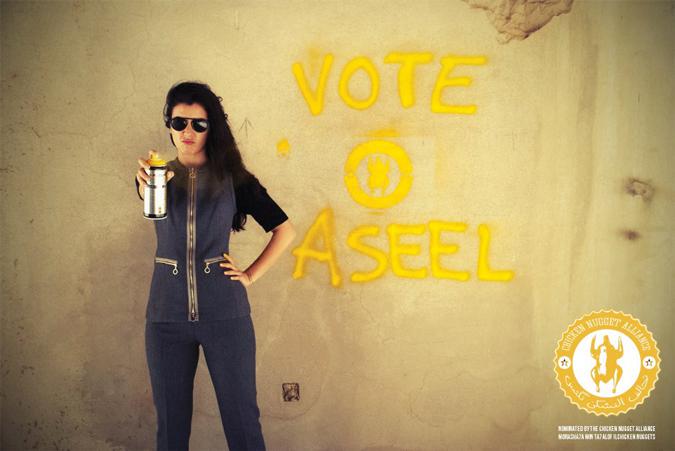

Her subsequent projects led her to create a mock political group, The Chicken Nugget Alliance, to represent Western educated, bilingual Kuwaitis as part of a residency with the British Council’s first Out of Kuwait program. In the final exhibition an election tent was set up at the Modern Museum of Art in Sharq. Using various mediums, she mocked the campaign system in which hearts and minds are won with passionate empty promises and by shouting catchy slogans.

When her second residency with Out of Kuwait began, AlYaqoub decided to move away from politics, and began to explore her society’s perception of itself. The students explored Kuwait, with visits to some of its greatest cultural and historical landmarks. AlYaqoub quickly realized that her country’s distorted collective memory of history was effecting the perception of their current self.

One year later, in the corner of the Edge of Arabia gallery in London, a small diwania with the traditional red floor cushions and silver dallah on a matching tray sat adjacent to an old tube television. The Kuwaiti family on screen went through their day-to-day lives. The son seemed to adhere to traditional norms as he dined and prayed with his parents. As soon as his parents left the room though, the young man replaced the traditional Um Kalthoum’s “Your Eyes Brought Me Back to the Days Past” with Elvis who sang “Kissin’ Cousins”.

For AlYaqoub, this has been the most difficult part of finding her cultural identity. The collective memory of her people is based on a reconstructed past, she says. While the Kuwaiti culture likes to think it was always quite conservative, they tend to forget the days when art and liberalism were very much a part of their lives.

“Our piece was a bit ironic as we were mimicking the ideas and memories of the past in a very traditional way,” she said. “It was directed to a Kuwaiti and Arab audience, or an audience that still holds tight onto memories, fantasies and stories of the past; the past in which they inherently did not belong to.”

In New York, her project, Mother Tongue was critiqued by colleagues and brought one unilingual English speaker to the realization that she needed to learn a new language. For AlYaqoub, this is why she creates art, and she hopes to enlighten many more on the differences in this world, and our unique places within them.

For more information on Aseel AlYaqoub’s work check out her website at http://aseel.carbonmade.com or follow her on Tumblr at http://aseelalyaqoub.tumblr.com