By Fatmah Al-Qadfan

Slamming doors and screeching neighbors woke me up every morning without fail. I would lay in bed listening to my host sister sing to her bawling baby and fervently wish that people would stop blasting their car horns at six in the morning. For about half an hour I would try to tune out the noise, focusing instead on the fast and furious plip plop plip plop of the rain. I wondered how my roommate could sleep through it all, sprawled out on the rickety bed next to mine. Eventually, shouts from the neighbors would escalate, thus relinquishing any hopes of sleep, and I would sit up in bed to start my Spanish homework. In Costa Rica, I did not need an alarm clock.

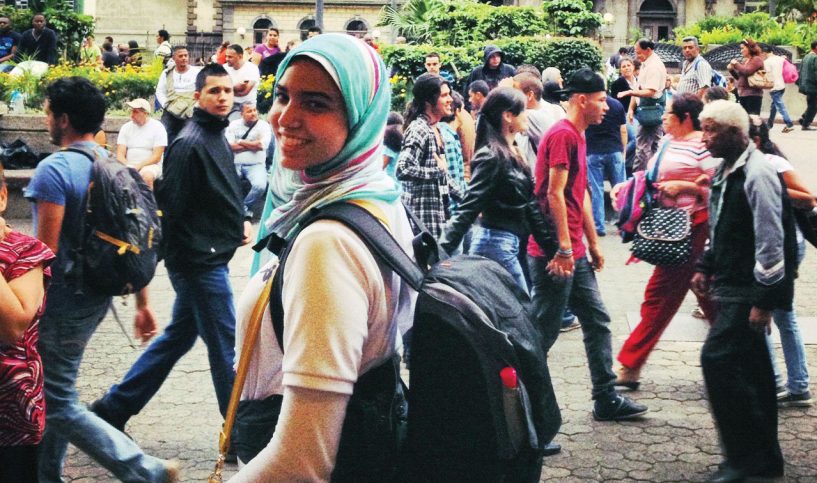

That’s how my days started while I was in Costa Rica: Spanish homework in bed until it was time to get ready for classes and work. For a couple of weeks (that somehow felt like a lifetime) I lived a different life from the one I lead in Kuwait. My days were long but not stressful, my food was significant but not substantial, and my only goal was to walk fast enough to avoid the daily tropical downpour.

I was staying with a Costa Rican family in Santa Martha, the residential district of San Pedro. My host family was made up of four generations of Costa Rican women. Add my roommate (an energetic young woman from Chicago) and myself to the mix and you have a cross-generational, international and multi-faith household. With five women and a baby in the house, the mornings were all about perfect timing, giving each of us a short window to use the single bathroom and hope for a little bit of warm water. I often wasted precious moments of my allocated time just surveying the premise for cheeky roaches that liked to dart out of their hiding places to taunt me.

Soft buenos días and smiles were exchanged during our morning routines. Mi mama Tica (my Costa Rican mother), Rocio, single-handedly raised three children with limited resources and lots of love. She struck me as a resilient woman, every bit a matriarch. Her dark hair was always pulled back in a tight bun and her plain shirts were serious. She wore a gold cross on a thin chain and would absentmindedly fiddle with it whenever she tried to understand my broken Spanish. Rocio’s mother, a small and spindly woman in her nineties made her way around with the aid of a steel walker. She spoke a universal grandmotherly language; every morning she saw my roommate and I out of the house with a prayer and a smile.

My host sister (Rocio’s daughter) also lived in the house with her temperamental baby girl. Between a full time job at a call center, a relationship, and raising a child, I was surprised that she had any time at all to look up Kuwait and Islam. She had a multitude of questions ready for me and I did my best to describe everything in Kuwait from the political system to cultural dos and don’ts, from machboos to shopping malls, parks and the economy. Once, I showed my host family the well-known Kuwaiti musical performances from the sixties and seventies. Despite the language barrier, the women were absolutely fascinated by the timeless performance and I felt a surge of pride and hope for my country, even though I was oceans away. Up until I came to stay with them, my host family had never met an Arab before and they waited for me to fill in the gaps or dispel myths embedded by Western media.

By the time Andrea and I sat down to eat, the baby would be napping again and my host sister would have left for work where she would spend another day answering the calls of grumpy customers in a different country. Breakfast was significantly quieter at Rocio’s. We ate warm servings of leftover gallo pinto and scrambled eggs. Sometimes there was bread and jam; sometimes there was a banana to share, but there was always a large pot of coffee on the table. And during those hectic mornings in Santa Martha, we were most thankful for the caffeine.